a Department of Health, Sta Cruz, Manila, Philippines.

b Field Epidemiology Training Program, Epidemiology Bureau, Department of Health, Sta Cruz, Manila, Philippines.

Correspondence to Sheryl Racelis (email: sherylqracelis@gmail.com).

To cite this article:

Racelis S et al. Contact tracing the first Middle East respiratory syndrome case in the Philippines, February 2015. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2015, 6(3). doi:10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.2.012

Background: Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is an illness caused by a coronavirus in which infected persons develop severe acute respiratory illness. A person can be infected through close contacts. This is an outbreak investigation report of the first confirmed MERS case in the Philippines and the subsequent contact tracing activities.

Results: The case was a 31-year-old female who was a health-care worker in Saudi Arabia. She had mild acute respiratory illness five days before travelling to the Philippines. On 1 February, she travelled with her husband to the Philippines while she had a fever. On 2 February, she attended a health facility in the Philippines. On 8 February, respiratory samples were tested for MERS-CoV and yielded positive results. A total of 449 close contacts were identified, and 297 (66%) were traced. Of those traced, 15 developed respiratory symptoms. All of them tested negative for MERS.

Discussion: In this outbreak investigation, the participation of health-care personnel in conducting vigorous contact tracing may have reduced the risk of transmission. However, being overly cautious to include more contacts for the outbreak response should be further reconsidered.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is an illness caused by a coronavirus whereby infected persons develop severe acute respiratory illness with symptoms of fever, cough and shortness of breath. The virus spreads from an infected person to others through close contact (droplet infection) such as caring for or living with an infected person; the incubation period is 14 days.1

As of 7 July 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 1368 laboratory-confirmed MERS cases, including at least 487 related deaths.2 The first case of MERS occurred in Saudi Arabia in 2012; cases have since been reported from countries in the Arabian Peninsula, Europe, North Africa, South-East Asia and the United States of America. The recent MERS cases in the Republic of Korea and China resulted from a single exported case with a travel history in the Middle East and subsequent human-to-human transmission.2

In February 2015, the first confirmed case of MERS in the Philippines was detected. This report describes the MERS case and the subsequent contact tracing activities.

An in-depth investigation form developed by Public Health England1 was completed using the case’s medical records and interviews with the health care workers (HCW) that cared for the case. Nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) and oropharyngeal swab (OPS) were tested for MERS-coronavirus (CoV) using real time-polymerase chain reaction at the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine.

Close contacts categories were identified as per the Philippines’ interim guidelines for MERS surveillance and contact tracing.3 Category A are passengers on the same flight as a confirmed MERS case seated in the surrounding three rows; Category B are passengers on the same flight as a confirmed MERS case seated in the surrounding three rows that travelled onto another country (i.e. transited in the Philippines only); Category C are those that lived with, worked with or cared for a confirmed case; Category D are close contacts of a suspect or probable case who died with MERS symptoms; Category E, developed during this investigation, included patients in the adjacent room of the health facilities of the confirmed case, all HCW from the facility where the case attended and all other passengers on the flight. The total number of contacts for each relevant category was gathered from quarantine officers, HCW and family members of the cases.

All contacts who were found were initially interviewed face to face using a standard close contact questionnaire headed by the Philippine Field Epidemiology Training Program investigation team and subnational surveillance officers trained in filling out the form; the patients from the adjacent rooms were interviewed over the phone. Contacts were then monitored daily for appearance of illness for 14 days starting from the date of last known exposure to the confirmed case. A standard symptom log sheet was used to record these details. Contacts in Category A, C and D were prioritized for MERS-CoV laboratory testing except for those HCW in Category C who had full personal protective equipment (PPE).

All Category E airplane passengers traced by the Philippines Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response Surveillance Officers Nationwide were also tested. The collected NPS/OPS specimens were all tested at the Philippines Research Institute for Tropical Medicine.

The index case was a 31-year-old female who worked as a HCW in Saudi Arabia. She was four weeks pregnant.

On 26 January 2015, she had rash, fever and cough and was diagnosed with hypersensitivity reaction in Saudi Arabia. On 1 February, she travelled with her husband to the Philippines while she had a fever. On 2 February, she attended Health Facility A (a health facility in the Philippines) as she had difficulty breathing, a productive cough and high-grade fever. She was initially seen at the outpatient department, transferred to the emergency department for admission and subsequently admitted in a private room. She was managed as a case of asthmatic bronchitis and was attended by the on-duty obstetrician-gynaecologist, pulmonologist and otolaryngologist. On 8 February, she still had persistent fever and cough. Her specimens were collected and tested for MERS-CoV. On 10 February, the test yielded positive results (Figure 1).

KSA, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; PHL, Philippines; RT-PCR, real time-polymerase chain reaction.

The patient was then transferred to Health Facility B, a designated MERS hospital, and was placed in an isolation room with negative pressure. She was attended by infectious disease specialists and obstetrician-gynaecologists; the rest of her hospital stay was uneventful with mild respiratory symptoms. On 19 February, the patient was discharged as she had remained afebrile for more than 48 hours and had two negative sputum and NPS/OPS tests for MERS-CoV. She recovered completely at home after her discharge with no known reappearance of fever.

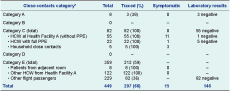

There were 449 close contacts identified: Category E (n = 359), Category C (n = 82) and Category A (n = 8). There were no Category B or D contacts. From these, 297 (66%) were found and 154 (34%) were tested or screened. The 15 contacts who developed symptoms all belonged to Category C (household members and HCW with direct exposure); all yielded negative results for MERS-CoV (Table 1).

HCW, health-care workers; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; PPE, personal protective equipment.

* Category A, Flight contacts within 3 rows of case; Category B, Flight contacts within 3 rows of case who travelled onto another country; Category C, contacts who lived with, worked with, or cared for case; Category D, close contacts of a suspect or probable case who died with MERS symptoms; Category E, patients in the adjacent room of the health facilities of case, all HCW from the facility where case attended and all other flight contacts of case.

We report on the investigation of the first confirmed case of MERS-CoV in the Philippines. A history of travel to MERS-affected countries and the appearance of fever and respiratory symptoms are critical clues to guide health providers to suspect MERS. The strong suspicion of MERS from the physician at Health Facility A led to an early diagnosis and perhaps averted additional cases. Upon laboratory confirmation, the confirmed case was immediately isolated upon at the designated MERS Health Facility B. This action may have reduced the risk of transmission to close contacts and the community. Urgent initiation of contact tracing activities by health-care personnel, quarantine officers and the investigation team may have also contributed.

Although there are still some gaps in understanding the risk of transmission of MERS-CoV, comprehensive contact tracing to prevent the occurrence of subsequent infections is recommended.4 According to the Philippines guidelines for MERS,3 close contacts of probable and confirmed MERS cases should be followed up and monitored for symptoms until 14 days after the last exposure; the usual definition for close contacts is those who lived with, worked with and cared for a confirmed case. At least one country’s department of health does not consider HCW using full PPE during exposure as close contacts and does not recommend laboratory screening for asymptomatic close contacts;5 however, in this investigation, Category E contacts were added. This may have been an overly cautious response and added burden especially as all contacts were then monitored for 14 days and tested even if they were asymptomatic. If these Category E contacts were excluded, then 94% of close contacts would have been traced. Whether to include Category E contacts in future investigations should be assessed, especially considering the additional burden that including an extra 359 contacts had on the response efforts.

Furthermore, in this investigation, all contacts who developed symptoms were Category C. As more than half of reported secondary cases of MERS were HCW,2,6,7 this group is strongly recommended for close monitoring and immediate testing. In this investigation, these contacts were tested for MERS immediately and had negative results.

None of the identified passengers from the case’s flight developed symptoms; to date, there had been no documented cases infected with MERS on board aircraft.8 However, the contact tracing of flight passengers is recommended. The European Centre for Disease Control recommends tracing the entire plane or at least seven rows on either side of the case;9 tracing those within two rows of a case was recommended by WHO for MERS case investigations.8,10

This investigation has some limitations as 34% of close contacts were unable to be traced, most of whom were passengers from the same flight as the confirmed case. Obtaining details of these contacts was difficult as not all passengers provided an address or phone number on their passenger arrival cards. Therefore their health status was not established, although there has been no reports of other MERS cases associated with this flight. A strength of the study was that all Category C contacts were traced.

There were no secondary cases reported from this MERS case, which may suggest that the response from the Philippines was effective. Factors that contributed to the large number of cases in the previous MERS outbreaks, including gaps in infection control in health facilities, crowded emergency departments, insufficient awareness of MERS by HCW and patients seeking multiple consultations11 were insignificant in this investigation. Exported cases of MERS are still likely, and therefore preparedness is required. The Philippines has established guidelines to direct the control and prevention of MERS cases.3

None declared.

None.

We are grateful for the cooperation and support of the Regional and Epidemiological Surveillance Unit of Calabarzon, the local government and Municipal Health Office of Laguna and Evangelista Medical Specialty Hospital. We would also like to thank the surveillance unit and laboratory staff of Research Institute for Tropical Medicine for testing the samples and assisting us in the investigation.