a Field Epidemiology Training Programme of Japan, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan.

b Infectious Diseases Surveillance Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan.

c Public Health Office, City of Sapporo, Japan.

Correspondence to Yuichiro Yahata (e-mail: yahata@nih.go.jp).

To cite this article:

Tabuchi A et al. A large outbreak of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157, caused by low-salt pickled Napa cabbage in nursing homes, Japan, 2012. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2015, 6(2)7–11. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2014.5.1.012

Objective: In August 2012, an outbreak of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) O157 infection was investigated by the City of Sapporo and Hokkaido Prefectural Government. The initial notification reported an illness affecting 94 residents of 10 private nursing homes distributed across multiple areas of Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan; at this time three cases were confirmed as EHEC O157 infection. The objectives of the investigation were to identify the source of infection and recommend control measures to prevent further illness.

Methods: A suspected case was defined as a resident of one of the private nursing homes in Hokkaido who had at least one of the following gastrointestinal symptoms: diarrhoea, bloody stool, abdominal pain or vomiting between 10 July and 10 September 2012. Cases were confirmed by the presence of Shiga toxin 1- and 2-producing EHEC O157 in stool samples of suspected cases. We conducted an epidemiological analysis and an environmental investigation.

Results: We identified 54 confirmed and 53 suspected cases in 12 private nursing homes including five fatalities. Of the 107 cases, 102 (95%) had consumed pickles, all of which had been manufactured at the same facility. EHEC O157 isolates from two pickle samples, 11 cases and two staff members of the processing company were indistinguishable. The company that produced the pickles used inadequate techniques to wash and sanitize the vegetables.

Discussion: Contaminated pickles were the likely source of this outbreak. We recommended that the processing company improve their methods of washing and sanitizing raw vegetables. As a result of this outbreak, the sanitation requirements for processing pickles were revised.

Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) causes gastrointestinal illnesses, resulting in symptoms such as watery diarrhoea, bloody stool, vomiting and abdominal cramps/pain.1 Among all reported EHEC cases, approximately 4% develop haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) and around 0.5% are fatal.2–4 The main route of EHEC transmission is via the ingestion of food contaminated with ruminant faeces.5 In Japan, EHEC infection has been a notifiable disease since April 1999, with 3500–4500 cases reported annually between 2012 and 2014 of which 2600 were symptomatic cases.2–4

On 11 August 2012, a possible EHEC O157 outbreak affecting the residents of 10 private nursing homes was reported to the Public Health Office (PHO) of the City of Sapporo and Hokkaido Prefectural Government. These nursing homes provide daily support with household tasks such as cleaning, laundry and meals but not medical care. They are distributed across a wide area of Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan. By law, staff at all facilities record details of all meals consumed by residents.

The initial report stated that 94 residents were affected, including three confirmed EHEC O157 cases and one fatal case. The PHO requested that the investigation be supported by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases. The objectives of this investigation were to identify the source of infection and recommend control measures to prevent further illness.

A suspected case was defined as a resident of a nursing home in Hokkaido with at least one of the following gastrointestinal symptoms: diarrhoea, bloody stool, abdominal pain or vomiting between 10 July and 10 September 2012. A confirmed case was a suspected case in which Shiga toxin 1 and 2 (stx1 and stx2)-producing EHEC O157 was detected in stool sample.

Public health nurses or food hygiene inspectors reviewed residents’ food records and conducted interviews with each of the 588 nursing home residents and 417 staff members. Information was collected using a standardized questionnaire which included demographics (sex, age), symptoms, date of onset and exposure history (e.g. food consumption and contact with ill patients) within 14 days before the date of onset. Food items in the questionnaires were adjusted to the specific menu at each nursing home.

All nursing homes had their own kitchen for the preparation and cooking of three meals a day for residents. Staff from local public health centres conducted a trace-back investigation of uncooked food items served during the two weeks before the outbreak to determine common food suppliers.

On 28 August, an inspection of one of the food suppliers was conducted by the PHO in accordance with the Food Sanitation Act,6 and the process of preparing the suspected food was replicated on-site on 7–8 September 2012. The concentration of sodium hypochlorite was monitored digitally.

From each of the 12 nursing homes, faecal samples from all residents and mandatory stored food samples served from 24 July to 5 August 2012 were collected. Frozen food, environmental samples and stool samples from 12 staff members were also collected from the food supplier during the initial inspection as required by law.6

All samples were tested at Sapporo City Institute of Public Health and Hokkaido Prefectural Institute of Public Health. EHEC O157 isolation and Pulse-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis were performed by Sapporo City Institute of Public Health, as previously described by Terajima et al.7

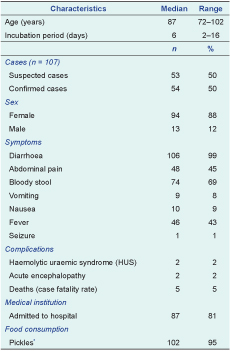

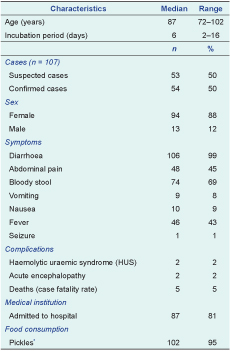

There were 588 residents in the 12 nursing homes and 54 confirmed and 53 suspected cases (Table 1); the overall attack rate among residents was 18% (107/588). The median number of cases per nursing home was eight (range: 1–19 residents).

* Pickles, low-salt pickled Napa cabbage.

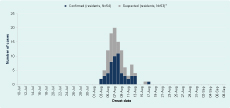

Of the 107 cases, 94 were women (88%) and the median age was 87 years (range: 72–102 years of age; Table 1). Among them, 106 (99%) reported diarrhoea and 74 (69%) had bloody stool. Two cases (2%) developed HUS and two (2%) developed acute encephalopathy. Five cases were fatal (case fatality rate: 5%); the median age was 95 years (range: 80–99 years of age). The onset of symptoms occurred during 3–17 August 2012, peaking on 7 August (Figure 1). No cases were reported after 17 August 2012. The median incubation period was six days (range: 2–16 days) from the time of exposure to the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms.

* Onset date of one case unknown.

One particular brand of pickles, made by Company A, was the only uncooked food item served that was eaten at all 12 facilities. The pickles were packaged on 30 July by Company A and served on 1 or 2 August at each nursing home and had been consumed by 102 cases (95%). No other food items were commonly served in all facilities. None of the care staff at any of the nursing homes consumed foods served to residents.

Of the 338 residents of 12 nursing homes that had stool specimens collected, the stx1- and stx2-producing EHEC O157 strains (eae positive and aggR negative) were isolated in 81 residents. The clinical case definition was met by 54 of the 81 residents.

Stored pickles were collected from two of the affected nursing homes and stx1- and stx2-producing EHEC O157 were isolated from both samples. The samples had been packaged on the same day (30 July) by the same food processing company according to the delivery records.

Twelve staff members of Company A also had stool samples collected; three were positive for EHEC O157. These three staff members reported eating the pickles, after which they developed diarrhoea, soft faeces or abdominal cramps between 4 and 5 August.

PFGE patterns from 11 stool samples from cases from six of the nursing homes, stool samples from two staff members of Company A and two pickle samples were indistinguishable.

The main ingredients of the pickles were Napa cabbage and salt with some cucumber and carrot. It took two days to prepare without a fermentation agent or vinegar. The product’s salt content is low (2%) and is served without washing.

During the replication process at the processing plant several issues were identified with the processing of the pickles: (1) during washing, running water could not circulate effectively around the leafy vegetables in the tank, and (2) the same sodium hypochlorite solution was used repeatedly about 10 times to sanitize the vegetables after washing; hence, the concentration of sodium hypochlorite gradually dropped (tank 1: from 250 mg/L to 100 mg/L; tank 2: 210 mg/L to 95 mg/L) during replication. The concentration of sodium hypochlorite was not checked or recorded at Company A during commercial production. Staff performed adequate hand hygiene procedures during production, including wearing gloves. Company A did not keep records on the source of the leafy vegetables or any other ingredients used in the manufacturing process, thus limiting the trace-back investigation.

On 11 August 2012, Company A suspended production and performed a recall. On 12 October 2012, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) revised the sanitation requirements for the processing of pickles.

This large common-source outbreak of stx1- and stx2-producing EHEC O157 was likely caused by the consumption of contaminated pickles at nursing homes. The pickles had been consumed by most cases, and most compelling, the same PFGE pattern was observed from nursing home cases, Company A cases and samples of the pickles.

That the onset dates of the cases from Company A occurred after the nursing home index cases were reported suggested that the staff members were not the source of infection or contamination. This is further confirmed by the adequate hygiene practice observed during the environmental investigation.

There have been similar outbreaks caused by low-salt pickles in Japan.8 Tsukemono, a traditional Japanese food, has a high salt content (around 10%) and is a naturally fermented pickle. Low-salt pickles,9 however, are very similar to tsukemono, but are not fermented. Low-salt pickles are becoming more common due to development of the cold chain during shipping and a general tendency of consumers to limit salt intake; however, they are similar to raw vegetables and therefore have a similar risk of cross contamination.10,11 In Japan, national guidelines recommend not serving raw vegetables in school meals due to the risk of contamination of micro agents such as EHEC and salmonellosis.12 However, nursing homes did not have such guidelines or regulations. As a result of this outbreak, we recommended that low-salt pickles should not be served in nursing home settings.

After this outbreak, the MHLW investigated the processing of low-salt pickles and found that only 6% of processing companies washed raw vegetable materials.13 As a result, on 12 October 2012, the MHLW revised the guidelines for the preparation for low-salt pickles and added the importance of sufficient washing and sanitization.

This investigation collected retrospective data and so there could have been some susceptibility to recall bias. As there was only one food common to all facilities, which was consumed by 95% of cases, an analytical study of food items was not warranted, especially as the laboratory evidence pointed to the pickles.

In conclusion, this outbreak was most likely caused by EHEC O157-contaminated pickles served at nursing homes. We recommend that raw foods not be served to vulnerable members of the population such as elderly people.

The investigation was conducted in accordance with the Food Sanitation Act.

None declared.

This investigation was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

We thank the Public Health Office of the City of Sapporo, Sapporo City Institute of Public Health, Hokkaido Prefectural Government, and Hokkaido Prefectural Institute of Public Health for their assistance in the epidemiological investigation and laboratory tests. We also thank Sunao Iyodad, Jun Terajima, and Makoto Ohnishi of the Department of Bacteriology I, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan for advice and technical assistance.