a Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), Beijing, 100050, China.

b West China School of Public Health, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China.

c Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China.

d Shanghai Pudong New Area Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shanghai, China.

e Guangxi Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanning, China.

f School of Population Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Correspondence to Weizhong Yang (e-mail: yangwz@chinacdc.cn) and Zhongjie Li (e-mail: lizj@chinacdc.cn).

To cite this article:

Yang W et al. A nationwide web-based automated system for early outbreak detection and rapid response in China. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2011, 2(1):10-15. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2010.1.1.009

Timely reporting, effective analyses and rapid distribution of surveillance data can assist in detecting the aberration of disease occurrence and further facilitate a timely response. In China, a new nationwide web-based automated system for outbreak detection and rapid response was developed in 2008. The China Infectious Disease Automated-alert and Response System (CIDARS) was developed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention based on the surveillance data from the existing electronic National Notifiable Infectious Diseases Reporting Information System (NIDRIS) started in 2004. NIDRIS greatly improved the timeliness and completeness of data reporting with real time reporting information via the Internet. CIDARS further facilitates the data analysis, aberration detection, signal dissemination, signal response and information communication needed by public health departments across the country. In CIDARS, three aberration detection methods are used to detect the unusual occurrence of 28 notifiable infectious diseases at the county level and to transmit that information either in real-time or on a daily basis. The Internet, computers and mobile phones are used to accomplish rapid signal generation and dissemination, timely reporting and reviewing of the signal response results. CIDARS has been used nationwide since 2008; all Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in China at the county, prefecture, provincial and national levels are involved in the system. It assists with early outbreak detection at the local level and prompts reporting of unusual disease occurrences or potential outbreaks to CDCs throughout the country.

Aberration of disease occurrence means the occurrence of cases is in excess of normal expectancy in a certain region. Early detection of the aberration of infectious disease occurrence and rapid control actions are prerequisites for preventing the spread of outbreaks and reducing the morbidity and death caused by diseases.

After China had an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, the government took efforts to enhance the capacity of infectious disease surveillance and successfully built the innovative web-based Nationwide Notifiable Infectious Diseases Reporting Information System (NIDRIS) in 2004. It enabled all the health care institutes across the country to report in real time individual case information of notifiable infectious diseases by Internet.1 This system shortened the interval between case diagnosis and case reporting to within one day on average. However, enhancing the timeliness of data reporting is only the first step for outbreak monitoring and response. Effectively analysing and interpreting the large volume of reported data and rapidly distributing the results to the responders are also key components. Therefore, a tool was conceived to conduct automated and timely analyses and detection of aberration of infectious disease occurrence to facilitate a rapid response to outbreaks and to effectively communicate the outbreak information among Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCs) in China. The universal availability of modern communication tools (such as computers, the Internet and mobile phones) in China also helped this idea to be realized.

In 2005, the China CDC, cooperating with the World Health Organization, initiated a national project to develop the China Infectious Disease Automated-alert and Response System (CIDARS). The system was successfully implemented and began to operate nationwide in 2008. This paper introduces the design and development of CIDARS and reports the preliminary evaluation of the system’s performance.

According to the Law of Prevention and Control of Infectious Disease in China, 39 infectious diseases are regulated as notifiable diseases. All cases of notifiable infectious diseases are diagnosed by clinicians using the uniform case definition issued by the Chinese Ministry of Health. A standard report form is used to collect a patient’s individual information, including name, gender, age, ID number, residential address, date of onset, date of diagnosis and diagnosis results. Since the implementation of NIDRIS in 2004, all notifiable infectious disease cases have been reported in real time directly from hospitals to the national infectious diseases surveillance database, located at the China CDC, Beijing, China.1 NIDRIS covers all health care institutions across the country, including general hospitals, specialized hospitals, township and village clinics and private clinics. According to the annual report on disease surveillance in 2008, approximately 67 000 health institutions reported case information to NIDRIS and about 5 million infectious diseases cases were reported annually.2

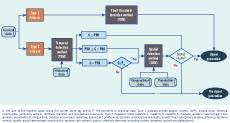

CIDARS was developed based on the existing data from NIDRIS; 28 types of disease (Table 1) that are outbreak-prone and require prompt action are included in the system. By integrating multiple aberration detection methods, CIDARS conducts real-time and daily analysis on the data and sends the abnormal signals to CDCs at the county level by short message service (SMS) using mobile phones. CDCs at national, provincial and city levels can also monitor the response process of each signal and provide timely technical guidance and support, if necessary. The system consists of four interconnected components: aberration detection, signal generation, signal dissemination and signal response information feedback (Figure 1). The unifying operational protocol of CIDARS on the workflow of these components was developed for the system users.

The three aberration detection methods were developed and applied in CIDARS in two stages. At the first stage, two aberration detection methods, the fixed-threshold detection method (FDM) and the temporal detection method (TDM), were developed in 2006. One year later, the third method, the spatial detection method (SDM), was added and integrated with the first two methods. The 28 diseases were classified into two types according to severity, incidence rate and importance. They were analysed with one of the three different aberration detection methods (Table 1). The three methods are briefly described as follows:

Type 1 diseases, including nine infectious diseases, characterized with higher severity but lower incidence, are analysed using FDM with the threshold of one fixed value.3

For type 2 diseases (more common infectious diseases), the moving percentile method was used to detect aberration of disease occurrence by comparing the reported cases in the current observation period to that of the corresponding historical period at the county level. To account for the day-of-week effect and the stability of data, the most recent seven-day period is used as the current observation period and the previous three years as the historical period.4,5 The number of cases in the current observation period was the sum of reported cases within the recent seven days. The corresponding historical period included, for each of the previous three years, the same seven-day period, the two preceding seven-day periods and the two following seven-day periods that resulted in 15 historical seven-day data blocks covering 105 days. We set the percentile of the 15 blocks of historical data as the indicator of potential aberration. The current observation period and historical data block were dynamically moved forward day by day.

One SDM, the SaTScan method, was used to search for spatial clusters of the incidence of type 2 diseases. SaTScan is a freely available spatial, temporal and space-time data analysis platform.6,7 This model was applied to the data at the township level. The population data required by SaTScan were obtained from the Chinese Bureau of Statistics, and the geographic data were from the Chinese Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research. When the incidence of disease in certain geographic areas (one town or more than one town) was significantly higher than that of other areas in the county, this area was categorized as spatial clustering.

Whether or not to generate a signal depended on the calculated results of these three aberration detection methods. The rules of signal generation are (Figure 2):

At least two epidemiologists in every CDC are designated to automatically receive the signals on their mobile phones by the SMS system located at the China CDC, Beijing, China. For type 1 diseases, the signal was distributed in real time, and for type 2 diseases the signal was released at 08:00 once a day.

The signal response process included two steps: signal verification and field investigation. The initial verification was conducted by epidemiologists in local CDCs by reviewing the reported cases in NIDRIS, completing a general assessment of information from other surveillance sources or directly contacting the reporting agencies. If the signal denoted one suspected outbreak after the initial verification, this signal would be determined as a possible positive signal, otherwise this signal would be determined as a negative signal. It is estimated that the verification of one negative signal may take about 10 minutes for one professional epidemiologist. Once a possible positive signal was determined, field investigation was conducted to confirm whether an outbreak was occurring.

The information on the signal verification and field investigation was fed back into CIDARS by local epidemiologists, so that the epidemiologists at the CDCs could actively monitor the outcome of signal verification and the evolvement of the outbreak.

China CDC took responsibility for the system design, development and maintenance as well as monitoring severe outbreaks. CDCs at provincial and prefecture levels took charge of the system’s user management within their administrative areas, daily reviewing and following up on the signals response process. All CDCs at the county level were responsible for receiving and responding to the signals, and promptly feeding the response results into CIDARS.

During the period 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2010, 221 counties from 10 provinces were selected to conduct the initial evaluation on CIDARS. For type 1 diseases, 308 signals were generated, involving nine diseases, 69 (22.4%) of which were identified as possible positive signals that triggered further field investigation, with nine cholera outbreaks confirmed. For type 2 diseases, 100 629 signals were triggered, including 19 types of infectious diseases, with about 4.4 signals per county per week on average. Among these, 1371 signals (1.36%) were verified as possible positive signals, and 167 outbreaks were finally confirmed by conducting field investigation. Generally, the percentage of possible positive signals to all signals of the respiratory diseases group (2.78%) was higher than that of zoonoses and vectorborne diseases group (1.95%) and food and waterborne diseases group (0.24%).

The development and application of CIDARS was one significant activity to enhance the capacity of early outbreak detection and rapid response in China. It has been integrated into the routine work of outbreak monitoring and response for all of China’s CDCs.

Compared to the manual analysis of surveillance data and reporting of unusual information level by level as done in the past in China, CIDARS greatly shortens the frequency of surveillance data analysis and that of outbreak communication among different CDCs. It also lessens the workload of data collating and analysing for epidemiologists to a great extent. The web-based system was developed and is maintained by the national CDC. The local CDCs only need to use their existing mobile phones, a computer and the Internet to receive and review the signals and transmit information. No new equipment was needed, which reduces the cost for local users.

Many outbreak early warning systems disseminate the signal by e-mail which may make it hard to confirm that the information is received successfully and in a timely manner.3,8,9 CIDARS uses an SMS platform and designates the specific mobile phones to receive the signal by short text message; the system automatically gets a confirming message which ensures accurate and timely dissemination. As opposed to some systems using only one-sided generation and distribution of the information, CIDARS has a good feedback function for processing signal responses and results to facilitate outbreak response cooperation and assistance, if necessary.

From the initial evaluation of the system, we find that CIDARS can quickly generate abnormal signals and effectively assist in the early detection and confirmation of some disease outbreaks, including both type 1 and type 2 diseases. However, the percentage of possible positive signals of all signals in CIDARS seems to be a little low. As we know, a low percentage of positive signals is a common deficiency facing many similar outbreak early warning systems.3,10–12 The percentage of possible positive signals varied among the respiratory, zoonotic and vectorborne, and food and waterborne disease groups, which demonstrated that different algorithms need to be considered based on the epidemiological characteristics of the disease.

Although CIDARS is a powerful and sophisticated system, one challenge is how to maintain normal operations of the system. Advanced computers with high-powered data calculation ability, the stability of Internet access as well as a professional system maintenance team are necessary. There are currently more than 6000 system users which raises the challenge of user management and training as staff turnover occurs.

One limitation of CIDARS is that it is hard to detect the outbreaks before the cases are diagnosed and reported by clinicians because the system is based on the notifiable infectious disease surveillance data. Therefore, CIDARS sometimes may be less timely and sensitive than some other outbreak detection systems using data on pre-diagnosis of cases in hospitals, media reports or school absenteeism. In addition, many negative signals are currently generated by CIDARS, causing unnecessary signal response for local staff.

Some improvements to CIDARS should be considered in the future. More flexible and reasonable algorithms and parameters for aberration detection should be developed and calibrated for the different characteristics of particular diseases and various needs of different areas in order to improve the performance of outbreak detection. New diseases could be added into the system by local users to address priorities in a particular jurisdiction. Finally, more systematic evaluations of the performance of the system should be conducted, especially on the feedback from users.

None declared.

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2002DIA40020, 2003DIA6N009, 2006BAK01A13, 2008BAI56B02, 2009ZX10004-201), and the China-WHO regular budget cooperation project (WPCHN0801617, WPCHN1002405).

We thank Dr Chin-Kei Lee (WHO Country Office in China) and Dr Archie Clements (University of Queensland, Australia) for giving comments and suggestions for improving this manuscript.